The legend of Lieutenant Columbo is built upon a foundation of deceptively simple contradictions: a cheap trench coat paired with a sharp mind, a beat-up Peugeot driven by a man of hidden wealth, and a polite “just one more thing” that served as the final nail in a killer’s coffin. Yet, to understand the man who inhabited that rumpled suit, one must look past the cigar smoke and the squint. Peter Falk did not merely play Columbo; he hollowed himself out and filled the character with his own fractures, transforming personal insecurity into a formidable cinematic weapon. The shambling gait, the apologetic rasp, and the seemingly aimless line of questioning were not just stylistic choices; they were a meticulously engineered facade designed to exploit the arrogance of the elite.

Falk understood a fundamental truth about power: those who possess it are often blinded by their own reflected glory. By presenting Columbo as a bumbling, distracted, and socially inferior figure, Falk forced his high-society antagonists to underestimate him. This was a psychological masterclass. While the audience saw a hero defined by decency and a saint-like patience, Falk was secretly channeling his own internal struggles—his deep-seated doubts, a simmering undercurrent of rage, and an insatiable hunger for the very approval he often pretended to disregard. He was a man playing a part within a part, using the lieutenant’s external “clutter” to mask his own internal chaos.

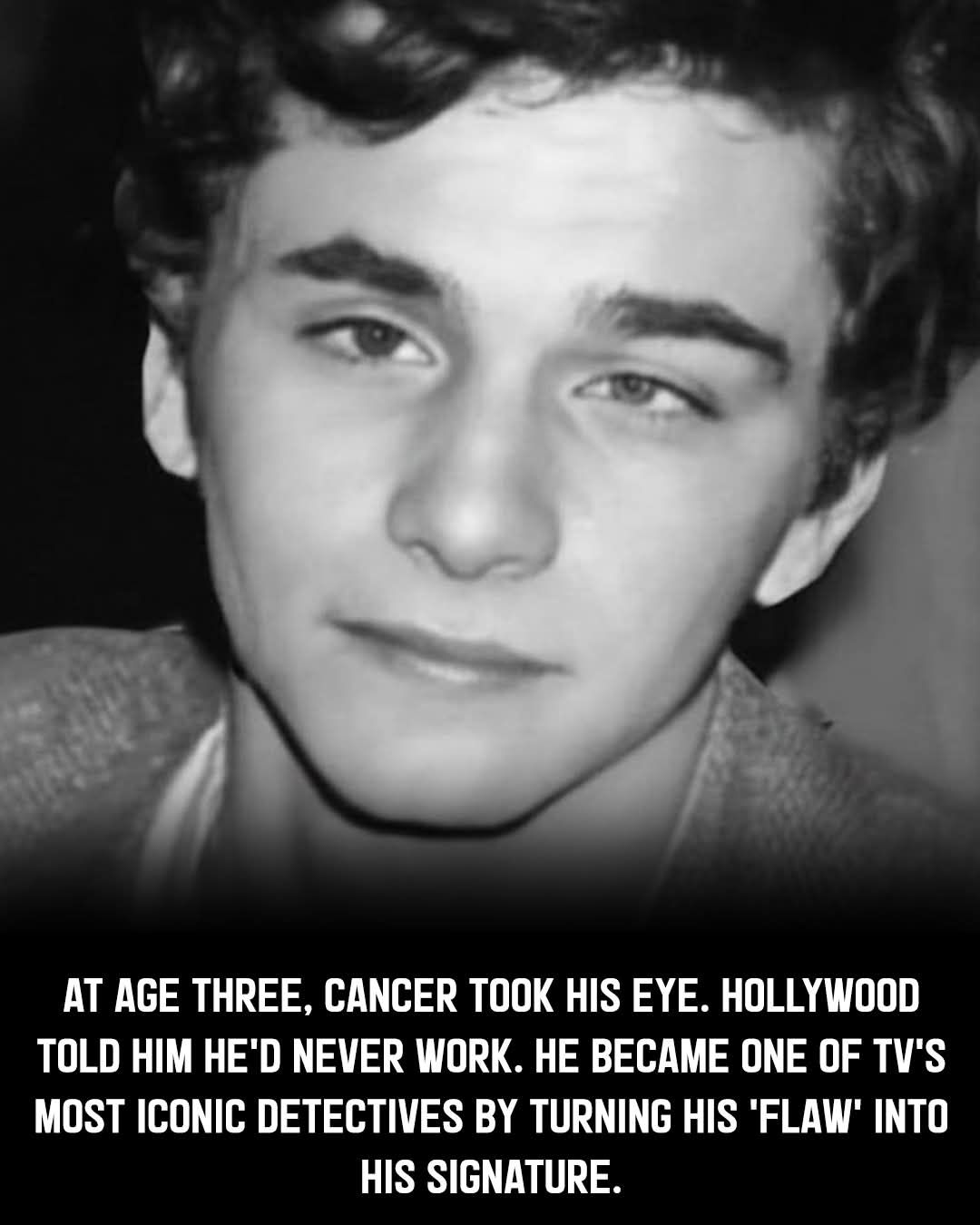

At the center of Falk’s physical and emotional identity was his glass eye, the result of a childhood struggle with retinoblastoma. Lost at the age of three, that missing eye became a permanent, physical marker of his “otherness.” On screen, it contributed to the famous, piercing squint that suggested a mind working three steps ahead of everyone else. Off screen, however, the glass eye functioned as a lifelong metaphor he could never truly escape. It left him with one eye perpetually fixed on the external world and the other turned inward, focused on a private landscape that was often bleak and uninviting. This physical reality ensured that Falk always felt slightly removed from the people around him—a spectator in his own life, watching the world through a lens that was both focused and fragmented.

SEE CONTINUES ON THE NEXT PAGE