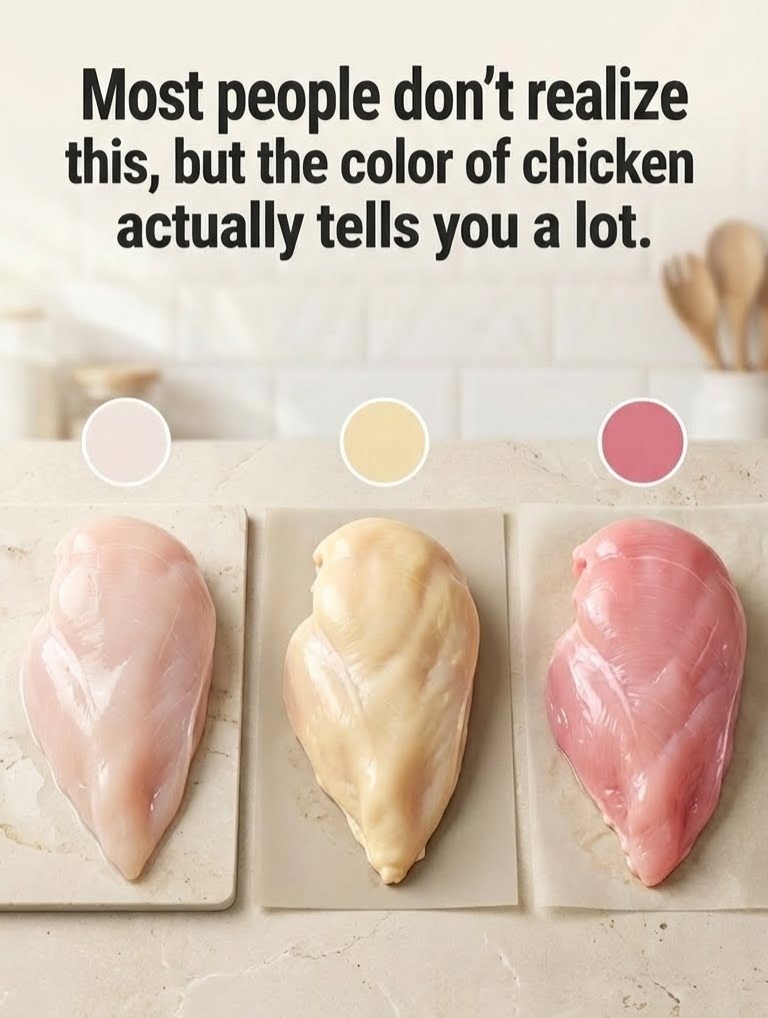

In the modern supermarket, the meat aisle often presents a quiet but complex visual puzzle that most shoppers solve instinctively without ever questioning the logic behind their choices. As you stand before the poultry section, you are met with a spectrum of hues: on one side, packages of chicken appear translucent, pale, and almost pearlescent pink; on the other, certain cuts glow with a deep, buttery yellow. While the price per pound might be similar, the stark contrast in appearance frequently triggers a internal debate. Is the yellow bird more “natural”? Is the pale one more processed? Or is the variation simply a result of clever agricultural marketing designed to manipulate consumer expectations?

To understand the truth behind the color of chicken, one must look beyond the plastic wrap and into the life cycle of the bird itself. Humans are biologically hardwired to judge the quality and safety of food through visual cues, yet in the world of industrial agriculture, color is rarely a straightforward indicator of health or safety. Instead, the shade of a chicken’s skin and fat acts as a narrative of its diet, its environment, and the speed at which it reached maturity. It is a visual record of a life lived, though it is a record that can occasionally be edited by those who produce it.

The pale, pinkish-white chicken that dominates the majority of grocery store shelves is typically the hallmark of the modern commercial farming system. These birds are bred for maximum efficiency, designed to reach a marketable weight in a remarkably short window of time. Their lives are characterized by carefully controlled indoor environments where movement is often limited to conserve energy for growth. Their diet is equally optimized, consisting primarily of high-protein grains that lack significant pigmentation. This industrialized process results in a consistent, affordable product that meets the massive global demand for poultry. While the lighter color does not inherently suggest that the meat is inferior in terms of safety, it does reflect a life cycle defined by speed and volume rather than the slow, natural behaviors of a foraging animal.

SEE CONTINUES ON THE NEXT PAGE